Features and Characteristics of the Klamath Basin

I am not a geologist, but I am fascinated how landscapes were formed. One cannot examine the Klamath River’s features and characteristics without looking at how it began. Alex Schwartz, of Herald and News (who has a better understanding of geology) is quoted here:

"Around 20 million years ago, North America began to stretch like taffy. The Earth’s crust expanded into what is now the Great Basin, forming thousands of parallel cracks running north to south.

As the stretched crust became thinner, heat from the Earth’s mantle pushed the fractured land upward, and it rose and fell along the small fault lines. This formed a vast network of mountain ranges and valleys called the “basin and range” that stretches from south central Oregon all the way to New Mexico.

This short video from the National Park Service shows how the basin and range was formed:

About 13 million years later, the oceanic Juan De Fuca Plate slid beneath the North American Plate. The subduction caused the Pacific Northwest coast to buckle upward, and pressure between the two plates forced magma to burst through that fold to form the Cascade volcanoes we see today.

The Cascades cut off the mountains and valleys of the basin and range from moisture that blows off the Pacific. But that didn’t stop water from flowing into what is now the Klamath Basin.

Pluvial lakes, whose levels depended on temperature and precipitation, formed throughout the western portion of North America. Basins became pools of water and mountains became islands within them. While glaciers in the northern Midwest were still at work carving the Great Lakes, the West was home to large, plentiful lakes.

Lake Modoc spanned nearly 1,100 square miles and covered all the flat lands of the Upper Klamath Basin with nearly 100 feet of water.

Lava flows from the Medicine Lake Volcano blocked the southern outlet of Lake Modoc through what is now Lava Beds National Monument. Once the lake reached its maximum level, it began slowly eroding a gorge to the west to form the Klamath River, the lake’s only outlet" (Schwartz, 2020).

The geology today is clearly guided by this, as the river flows out of the western edge of the Great Basin across three mountain ranges, going through a number of geomorphic provinces. The portion of the Upper Klamath Basin located upstream of Upper Klamath Lake drains two geomorphic provinces: High Lava Plains and Modoc Plateau, composed predominantly of Miocene age basalts. Low channel gradients, limited surface runoff, and internal drainage contribute to a muted hydrologic response to storm events and low sediment yield to the Klamath River.

The Klamath River downstream of J.C Boyle Dam flows through three distinct geomorphic provinces: the Cascade Range Province, the Klamath Mountains Province, and the Coast Range Province. The Cascade Range Province, comprised predominantly of andesitic volcanic rocks of Cenozoic age. The High Cascades Sub-Province is younger (Quaternary age) and is distinguished by lava flows, lava shields, pyroclastic flows, tuffs, cinder cones, and classic cone shaped stratovolcanoes.

The Mid-Klamath Basin occurs predominantly within the Klamath Mountains Province and is underlain by a series of geologic terranes comprised of accreted oceanic lithosphere, volcanic arcs, and mélange. These rocks are more resistant to weathering and form high-relief terrain with prominent peaks and ridges.

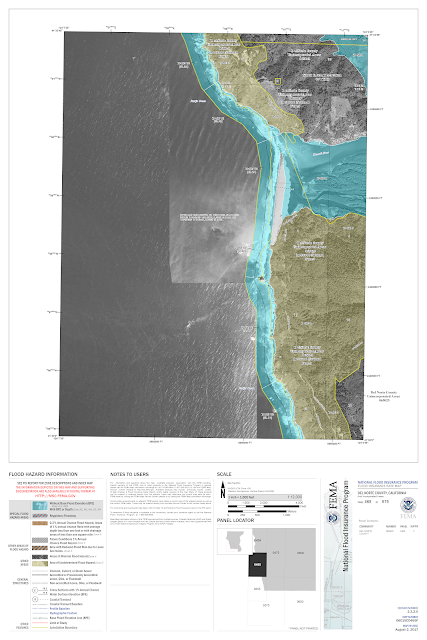

The Lower Klamath Basin occurs farther west within the Coast Range Province and includes 40 miles of the Klamath River from approximately the Trinity River confluence to the Pacific Ocean. The combination of tectonic deformation and shear, compositionally weak bedrock, and high precipitation rates in the Coast Ranges result in high erosion rates and sediment yields compared to other parts of the Klamath Basin (California Water Board, 2018).

The incredibly diverse geographic features effect the equally diverse dendrology of the region which will be explored in a later post.

But another feature of the Klamath is its aquatic life. The Klamath River once supported the third most productive salmon run on the West Coast of the United States while Upper Klamath Lake supported robust populations of Lost River and shortnose suckers. Not only does the reviver run down stream through three mountain ranges, but the salmon used to climb over these ranges The salmon used to run from the ocean all the way to the lakes of the basin. Now they are in decline, including spring-run and fall-run Chinook salmon, and there are several species of fish that are listed under the Endangered Species Act, such as Lost River and shortnose suckers, bull trout, and coho salmon.

Bull Trout

These fish represent critical spiritual, cultural, and economic roles to the Tribes of the region, and I hope to talk to one or more representatives of the Yurok Tribe about how the dam removal can and may aid in the regeneration of these species. And yet these remarkable fish and other species have and continue to be affected by sustained drought in the region. The water will flow freely in the near future but there has to be water (Guertin, 2022)

Comments

Post a Comment